|

On December 30, 1903 a milliner from Madison, Wisconsin and a friend

,reported only as J. Turner,▼1 attended a fateful matinee of Mr. Bluebeard

at Chicagoís new luxury playhouse, the Iroquois. When a fire raced from the stage

to the balconies, Myrtle and Mr. Turner were not among the nearly six hundred

who died. As with a majority of first-floor occupants, they escaped easily.

|

|

|

Myrtle Eva Grant (1878–1973) was a twenty-five-year-old Milwaukee native who worked for the Burdick-Murray

dry goods store in Madison.▼2 She had visited her family in Milwaukee over the Christmas holidays,

then traveled south to Chicago. Her other activities in Chicago were not reported. In general, newspaper

references to Myrtle, as well as her family, are sparse. They seem to have been a very private family.

Newspapers in the late 1800s and early 1900s gave up columns of space for "visit lists." Each entry was a one- or two-sentence notice of so-and-so visiting a friend or relatives in xyz town.

I'm not talking here about a habit of the wealthy; teachers, salesmen Aunt Bea and cousin Sue kept the world apprised of their weekend plans, major trips, shopping trips to nearby cities. The reason for it is a mystery to me, but in working

on this project I've often found useful hints in the blurbs. Wish the Grants had done it.

An example:

|

|

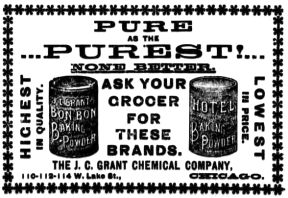

In addition to her millinery occupation Myrtle

served as secretary-treasurer for her fatherís company, Grant Chemical, later named J.C. Grant Chemical. Her parents

were Alexander and the late Julia German Grant. Julia had died in 1900 of spinal meningitis. Alexander was a

Civil War veteran and former teacher.

In the years after the fire

Myrtle continued working for Burdick-Murray for a few years, but in 1910 lived in Milwaukee with her father and siblings.

In 1913 she relocated to New York City to

work for Phipps Millinery, for only a short time, I think. The following year she moved to Chicago and married William Wizner. She remained an officer in Grant Chemical until at least 1914.

Grant Chemical produced farm implements in the late 1800s but by 1900 concentrated on baking powder, with

production in St. Louis and offices in Chicago.

In 1920 the company was sold to Calumet Baking

Powder of Chicago (still on the market,

owned by Kraft). Myrtleís father died the following year, possibly indicating that his health had something to do with the decision to sell to Calumet.

The Wiznerís settled in California, had three

or four children, and celebrated their

fifty-seventh wedding anniversary. Myrtle lived to age ninety-five.

|

|

From 1879 to 1920 Grant Chemical's Bon Bon and Hotel baking soda brands were among many targeted by a

deceptive anti-aluminum campaign waged by the Royal company. The Grant Chemical advertisement above first appeared in 1898 and

ran until 1910 in Chicago and other newspapers, on pages directed to the trade rather than homemakers.

Grant Chemical's resistance

Aluminum sulfate gave performance properties to baking powder that Royal's cream-of-tartar formulation could not match, and, because aluminum sulfate reduced the amount of baking soda needed, for a reduced cost.

In an era in which people ate a pound a day of bread, ingredient costs mattered. An energetic response from Royal was predictable. The dishonesty of Royals' response, however,

earned a place in the history of marketing scumbaggery that has been exposed in books and articles ever since. Google "baking powder wars" and you will find many interesting online discussions.

Royal bribed officials, lied to the media,

engaged in industrial espionage, and lied to

their customers. Under the circumstances, Grant Chemical's decision to use it's ad expenditure to market to the

trade was wise. Once GC's Bon Bon baking powder reached grocery stores, its lower price won the first battle.

When the product reached kitchens, improved baking experiences won the war. Royal didn't disappear but was eventually forced to add an aluminum-sulfate brand to its line.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

1. Might have been John C. Turner, a dry goods salesman that was mentioned in a newspaper blurb about a Grant family summer outing.

2. In 1903 the Burdick-Murray store in Madison, Wisconsin was just three years old.

|