|

|

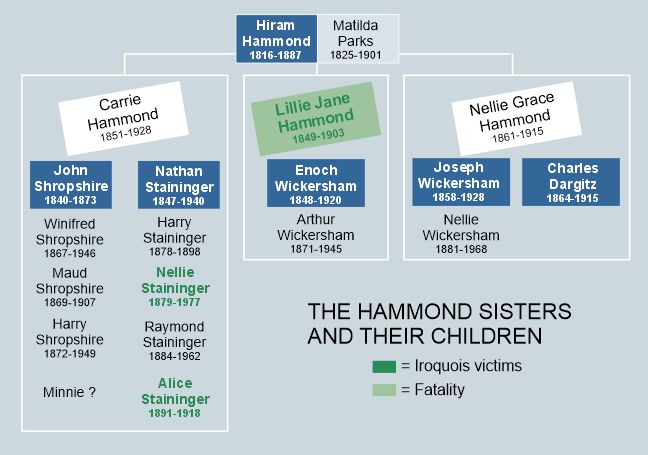

|

|

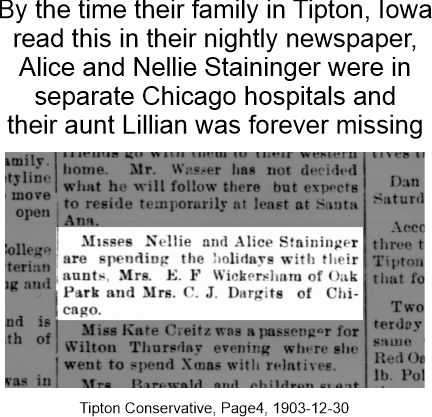

On Wednesday December 30, 1903, fifty-four-year-old Lillian Hammond Wickersham▼1 went to

Chicago's newest luxury theater, the Iroquois on Randolph St., with her two nieces. Nellie▼2

and Alice Staininger were in Chicago visiting from their home in Tipton, Iowa

where big shows like Mr. Bluebeard did not appear.

Lillian was one of three Hammond sisters. The other two, Carrie Staininger, the mother of Alice and

Nellie, and Nellie Dargits lived in Iowa and Chicago. While in Chicago, the girls first stayed with their aunt

Lillian and she was going to join them that night for a visit to their aunt Nellie Dargits.

At the Iroquois, according to Alice, the women purchased seats in the second-floor balcony but the

usher took them instead to the north side of the third floor gallery.▼3

Soon after the start of Act II a fire appeared on the stage. When it began spreading to

the auditorium, the three women left their seats and were soon separated by the crowd. Alice went

out the fire escape exit onto the landing and with the limber agility of her youth climbed down the

railing beneath the steps as far as possible and hung there until rescuers held a ladder for her to

descend the rest of the way, while a fire hose lightly sprayed her. Nellie was knocked to

the floor inside the theater and became caught beneath the feet of others in the crowd. The backdraft was minutes away and she would have died there on the floor but for a man she described as having an inflamed head.

She too headed out a fire escape exit. All three women were said to have stood up from their

seats at the same time but Lillian did not follow the girls to the fire escape exit.

Seems likely Nellie spent the rest of her life

wondering if her rescuer survived.

Both girls suffered non-life-threatening burns to their faces and hands. Alice was taken

to St. Lukes Hospital and Nellie to the Samaritan Hospital. Lillian's husband and son, Enoch Wickersham

and Arthur Wickersham, and

her sister, Nellie Dargits, began searching hospitals and morgues immediately. The night of the fire

they first found Alice, then at midnight Nellie, but nine days later Lillian Wickersham's body was still

missing.

By then only four unidentified bodies remained and police advised the Wickershams that Lillian had

almost certainly been misidentified by another family who had no idea they had the wrong woman.

See notated

January 8 1904 article in Inter Ocean newspaper — the only mention of Lillian's missing

remains that appeared in Chicago newspapers. (Crickets at the Chicago Tribune.)

Correcting body mix-ups wasn't easy

Two well-to-do families who could not find the remains of their young sons had been able to find their missing

family members by hiring private detectives to cull through victim descriptions for families who might have

buried the wrong person, then talk to those families to further narrow the possibilities. They then

employed attorneys to arrange and finance exhumations. I don't think the Wickershams could have afforded

such services but even if they'd had the resources, there were other obstacles to finding Lillian's remains.

The successful location of the sons had involved young male children. In that age/gender category of Iroquois

fatalities there were twenty-three victims to cull from. In Lillian Wickersham's category, there were

seventy-eight, some so severely injured that Nellie Dargits described the corpses as impossible to tell what

they were, least of all who. I take that to mean it was difficult for a non-medical person to determine if they

were male or female, twenty-five or sixty years old, slim or obese.

At this moment (Apr 2025) I know of only two incidents of missing remains among Iroquois victims. Lillian Wickersham is one and the other was a teenage girl. An unidentified family in Madison, Wisconsin,

(possibly Eva Hire's only because the other Madison burials of young females were slightly less likely) buried a girl

they thought was their daughter and it turned out to have instead been

Carolina Ludwig.

That happened two months after the fire, by which time the only remaining Iroquois victim body was that of

the barely injured unidentifed fifty-ish woman that had been viewed by hundreds of families and was eventually

buried at Montrose cemetery. No chance for the Madison family to retrieve the correct remains for their

daughter. Like Enoch Wicksham, they had no choice but to accept it.

The lack of attention to Lillian's missing body by Chicago newspapers was extraordinarily odd. Had she been found

and for some reason the discovery didn't make it to newspapers? Tipton, IA newspapers gave ample space to the

search for Lillian' but it was as if a switch was flipped on January 9 and Lillian's disappearance disappeared.

Years before the Iroquois fire, Lillian's father, Hiram Hammond, had purchased space #14 for his family in

the Masonic Cemetery in Tipton, and in it plot #6 was allotted to Lillian. There is no tombstone and extant

records list her date of death but not a burial date. Some Googling tells me it is not uncommon for a

cemetery to record death dates of non-interred plot owners. I spoke with an administrator of Tipton

cemetery records who confirmed that the 12/30/1904 death date had at some time been recorded for Lillian, but

not a burial date. I also spoke with helpful folks at the Cedar County Historical Society who helped me find

more information about the families but they did not have anything about a memorial service for her.

Additional in-progress discussion of the unidentified and missing

|

|

|

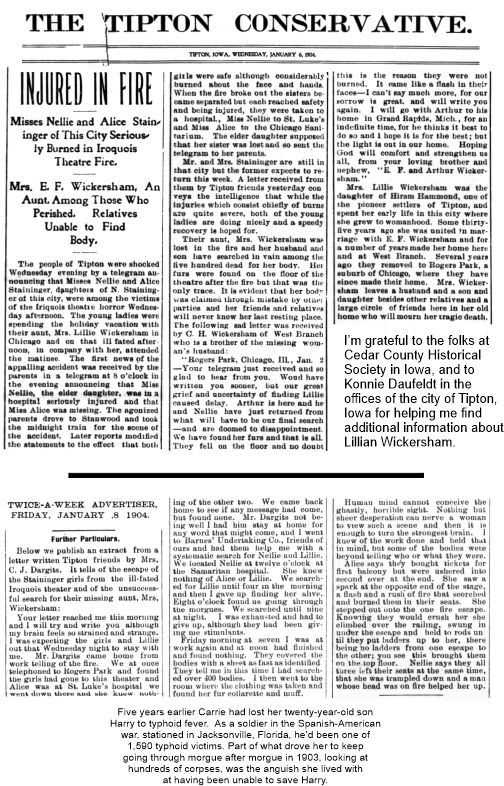

Enlarge to read details of the morgue search for Lillian's body and

Alice's jungle-gym escape

|

|

Lillian, Carrie, and Nellie were the daughters of Quaker parents, the late Hiram and Matilda Hammond.▼4

Lillian and her husband Enoch Wickersham, like Nellie and Charles Dargits, had just one child.

Carrie was the Mother Hubbard of the sisters. Though she reported only four in the 1900 U.S. Census, perhaps thinking

the question on births only applied to those with her current spouse, she seems to have had seven or eight children,

including a a son who died in the Spanish-American war.

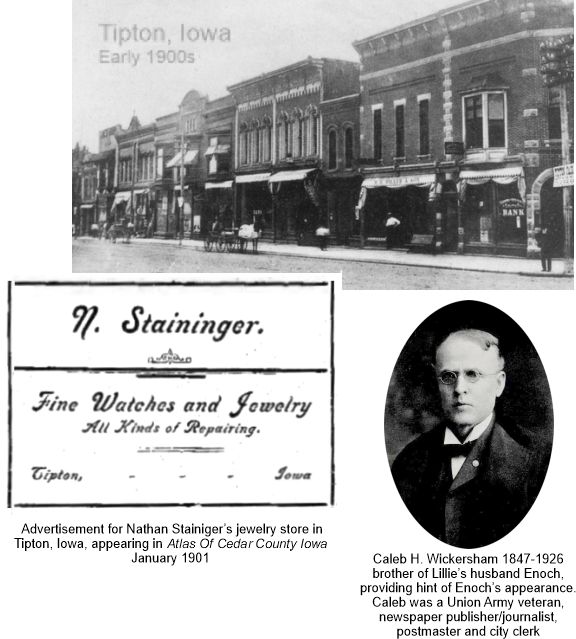

Nathan Staininger, a jeweler, was Carrie's second husband (her first, John Shropshire, had died in a gruesome

train yard accident). Her sister Nellie Hammond was also on a second marriage. Her first, to her

brother-in-law, Joseph Wickersham, brother of Lillian's husband Enoch, had ended in divorce, but she got a daughter

out of the deal.

All the Hammond girls lived in the Tipton, Iowa area until 1900, some moving west to Denise, IA, others east to Chicago,

some remaining in Cedar County, and some returning to Tipton in their later years.

Tipton, Iowa

With thirty-one-hundred residents, about five hundred more people live in today's

Tipton than did in 1900, but

the community is no longer served by two railroads. Located about midway between Chicago and Des Moines,

and between Minneapolis and St. Louis, in pre-automobile days rail service gave Tipton access to four major

cities. The train ride to Chicago for Nellie and Alice took ten to twelve hours.

|

|

In the years after the fire

Alice Staininger's short life

Around the time of the Iroquois fire the Stainingers moved to Denison,

Iowa. In 1911 Alice married a St. Louis man, William Gates, and they had a daughter named Virginia

Eloise Gates. In October 1918 twenty-seven-year-old Alice and five-year-old Virginia were visiting friends in Sioux

City, Iowa when Virginia became ill. She recovered but her mother caught a cold and died of a heart attack.

Two weeks before, the 1918 pandemic hit Fort Dodge, a couple hours away. It took the lives of seven hundred soldiers

and, my guess, a young mother who had once jungle-gymned her way to safety at the Iroquois theater.

Arthur S. Wickersham Lillian's only child, had three wives and five children. He named his first-born

daughter after his mother. I did not find much information about Arthur. In 1903 he was in charge of the silk department at the Boston Store in Grand Rapids. In subsequent years he worked as a

traveling salesman selling silk. In an interview with the Grand Rapids Press Arthur confirmed something I'd assumed. Depending on the date, some funeral homes were so full of bodies that they could not

physically separate the identified from the identified. They covered the identified bodies with blankets and admonished viewers not to remove the blankets. Some funeral homes, especially as more bodies were

claimed and removed, were able to put identified victims in a room separate from the unidentified. Arthur Wickersham felt they could have found his mother if they'd only been able to view the identified bodies.

Enoch Frankin Wickersham, Lillian's husband, remarried four years after Lillian's death, to a woman twenty years

younger: Emma L Brandfas (1870–1942) They remained in he and Lillian's house on Estes in Rogers

Park for awhile.

Lillian's niece Nellie Staininger remained in Denison, IA, worked as a clerk in

a plumbing shop in 1920 and in 1930 with her cousin Nellie Grace Wickersham (who used the name of her

stepfather, Dargits). Nellie Staininger than went by Nell and Nellie Grace by Grace. Nell lived to age

ninety-eight. She did not marry.

|

|

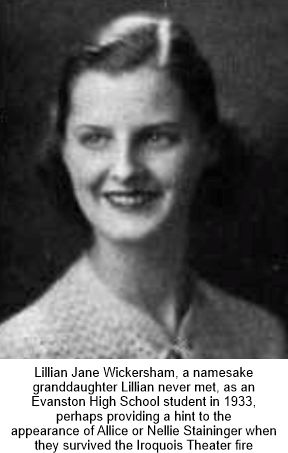

Granddaughter Lillian Jane Wickersham (pictured)

Lillian's granddaughter was feisty, full of life and a feminist before the term existed. An edited-for-privacy version

of her obituary.

|

|

Discrepancies and addendum

1. Aka Lillias (probably her birth name),

Lillie, Lily and Liddy.

2. There are three women named Nellie in this family: a.) Nellie Grace Hammond Wickersham

Dargits, who was one of Lillian's sisters, b.) her daughter, Nellie Grace

Wickersham, and c.) Nellie Staininger, Lillian's niece. Refer to

family tree chart below.

3. A discrepancy between Alice's account of their seat location and a statement in a published interview

Arthur Wickersham gave to the Grand Rapids Press GRP raises a question about the location of their seats that I doubt will ever be answered. An Iowa news story quoted Alice as saying that they purchased

tickets for the balcony on the second floor but were ushered to the third floor. Reportedly Arthur said the girls went out the fire escape exit with an unfinished step. That step,

evidenced in a day-after photo, was at an

exit on the second floor, not the third. The GRP reporter, or Arthur Wickersham, might have

inserted the reference to the unfinished step to juice the story. Prior to testimony at the Coroner's inquest clarifying

there was only one unfinished step, sweeping news stories implied that none, many, or most of the fire escape steps were

unfinished. So embellishment is a possible explanation for the discrepancy. Another is that the single sentence about Alice's remark that they'd been ushered to the wrong floor may not have been the entirety of her statement. In a paragraph at the end of

a long story, with tell-tale signs of copy-fitting condensing, GRP reported, "Alice says they bought tickets for first

balcony but were ushered into second over at the end." Alice might actually have said, "We bought tickets for the first

balcony but were ushered into the second, over at the end. Aunt Lillie objected and they took us to our correct seats."

Such an edit would offer a plausible explanation. (The faulty step was a consequence of a last-minute architectural

change in the balconies that shifted the location of that fire escape door opening upwards, thus requiring an accordant adjustment

in the layout of the fire escape stairs, an adjustment that was not made.)

4. Hiram's first wife, Louisa Ann Parsons, with whom he had a daughter, passed in 1847 and he married

Matilda "Millie" Parks a year later. With a rake-manufacturing company to run, he needed a wife

and mother for he and Louisa's daughter, Augusta Hammond (1840–1897), who was seven to eight years old

when her mother died. They lived then in Camden, New York and relocated to Iowa sometime in the next decade,

probably following Hiram's brother Willard who had settled in Tipton in 1842.

|

|

Story 3041

|

|

|